In 2002 or so, Thom Jones published an article in GQ Magazine.

Though a superficial Google search yields no evidence, I know I read it, unless, like so many of Jones’ protagonists, my mind has turned cloudy and unreliable, prone to hallucination and fabrication.

It was a short and entertaining piece about what it’s like to be in a street fight, and, importantly, the distance between that reality and most men’s Hollywood-conditioned ideas of it.

A real fight, Jones explained, is not cleanly landed blows and choreographed precision. It’s knees to the groin, scratched eyes, torn shirts, the crunch of bone on bone.

He said something to the effect that there are very few men out there who actually know how to conduct themselves in a fight. And then ended with a killer last line, something like:

“And, no. You’re not one of them.”

It’s a cutting dismissal, aimed perfectly at a readership that surely imagines fighting–along with rapping and stand up comedy–as an endeavor at which it would undoubtedly excel if only given the chance.

Here, Jones evinced a level of self-awareness. Tough Guy Lit is, in general, not read by actual tough guys. There is a vicarious fascination at play.

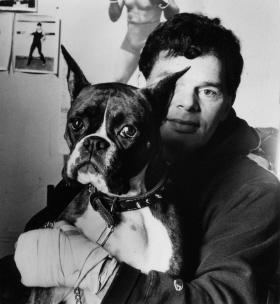

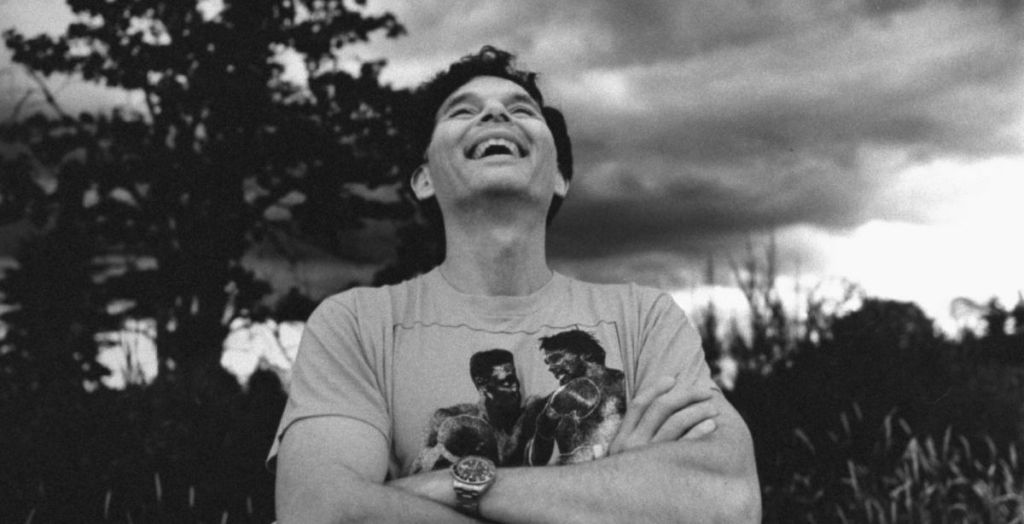

And Jones’ tough-guy backstory was minor legend in 90’s literary circles. The working class son of a professional boxer who committed suicide, he became an amateur fighter himself and later a Marine, but was KO’d so thunderously in a Marine Corps bout that he developed epilepsy, the dark psychic complications of which would plague him thereafter (in his second book’s acknowledgements, Jones thanks the manufacturers of Effexor and Elavil, “drugs so good they feel illegal.”)

He went to the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and worked a succession of odd jobs, finally and famously breaking through when he was in his forties and working as a high school janitor.

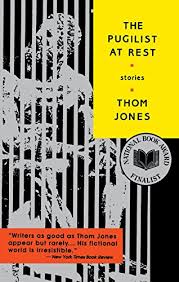

He published three acclaimed short story collections between 1993 and 1999–The Pugilist At Rest, Cold Snap and Sonny Liston Was A Friend Of Mine–then all but disappeared, plagued by deteriorating health until his death in 2017.

Jones’ fans might concede that his work sometimes seems a reflection of his colorful personal mythology–boxing, Vietnam, mental illness and various forms of depression and compulsion are recurring themes–but we’re not talking about confessional realism here, nor is this “pulp,” a simplistic and inapplicable designation.

What I’ve always loved about Jones’ stories is their mordant–and morbid–lyricism. Some of my favorites read almost like broad comedy given a grotesque spin.

“40, Still At Home,” is about an out of work engineer who is–you guessed it–40 and still at home, a burden to his aged mother. He is a bleaker Ignatius J. Reilly, a self-pitying, grandiose slob whose fortunes turn when the story veers into near-Stephen King territory–minus the gore, plus a wicked sense of humor.

“Mouses” (also from Sonny Liston), centers around another unemployed mid-career schlub who, after finding his kitchen invaded by mice, slowly transforms into a kind of low-rent Caligula, catching, breeding and fighting the rodents against each other in tiny gladiator matches.

These stories are dark, sure, but also laugh out loud funny–uniquely bugged-out reports from the underside of Fortuna’s wheel. An air of fatalism–one thick with sweat and cigarette smoke–pervades much of Jones’ work (Schopenhauer and Nietzsche are favorite touchstones), but he offers up a sense of hopeful spiritual yearning just as frequently. The kind of shining optimism known only to the damaged and disavowed.

Though he spends a good amount of time on the philosophical edge of barbarism–often in the zero-sum worlds of boxing and soldierhood–Jones travels a considerable distance in his stories. It’s not all Scorcese-like meditations on masculinity and violence.

“Rocketfire Red” is about an aboriginal Australian girl who improbably becomes an international supermodel. “A White Horse” and “Quicksand” feature a character known only as Ad Magic, a copywriter who suffers epileptic fugues and tends to wake up disoriented in far-off locales.

“Daddy’s Girl” and “I Want To Live!” are both told from the POV of elderly women, the former recounting her family’s history in epistolary form, the latter describing a (by-definition) losing battle with terminal illness, written in Jones’ less-favored third person.

I discovered Jones by chance while browsing my college’s library many years ago. The title, referencing one of boxing’s most notorious Guys You Don’t Want To Meet In A Dark Alley, accompanied by the image of a battered iron bell, triggered a Pavlovian response in my late-adolescent brain. I was the kind of vicarious tough guy aspirant Jones would later set straight in that GQ article.

Leafing through his books for the first time in years, I wondered how they’d hold up in these modern times. And I think the answer is, better than ever. After twenty years of television as the dominant artistic medium, and those filled with antiheroes and non-stop attempts at hardbitten humor, these stories endure. They’re the real deal.

Quirky darkness is the rock upon which prestige cable has repeatedly flung itself these many years. When it works, we get something of this caliber, something dark and funny–nihilistic, but in a fun way!–a Breaking Bad, say. When it fails, we get middlebrow horseshit like True Detective and Ozark.

Though it is my firm belief that we are entering a future in which absolutely all human experience will be turned into a limited streaming series, I actually hope they never option these three collections. They’re too good, too real, too special.

I have always wanted to be a good writer, but often worried in private that I have not suffered enough to make it so (JV-level angst, I know). I spent a good year of my early 20’s trying to write like Thom Jones. I figured never having been a boxer, Marine, mental patient or anything approaching a tough guy constituted minor, fungible details.

But as Charlie Parker said, “If you didn’t live it, it won’t come out your horn,” which is why I now find myself writing about Thom Jones, rather than like Thom Jones.

It’s all for the best.

Unless that GQ article is indeed a figment of a troubled imagination, I take Thom at his word.

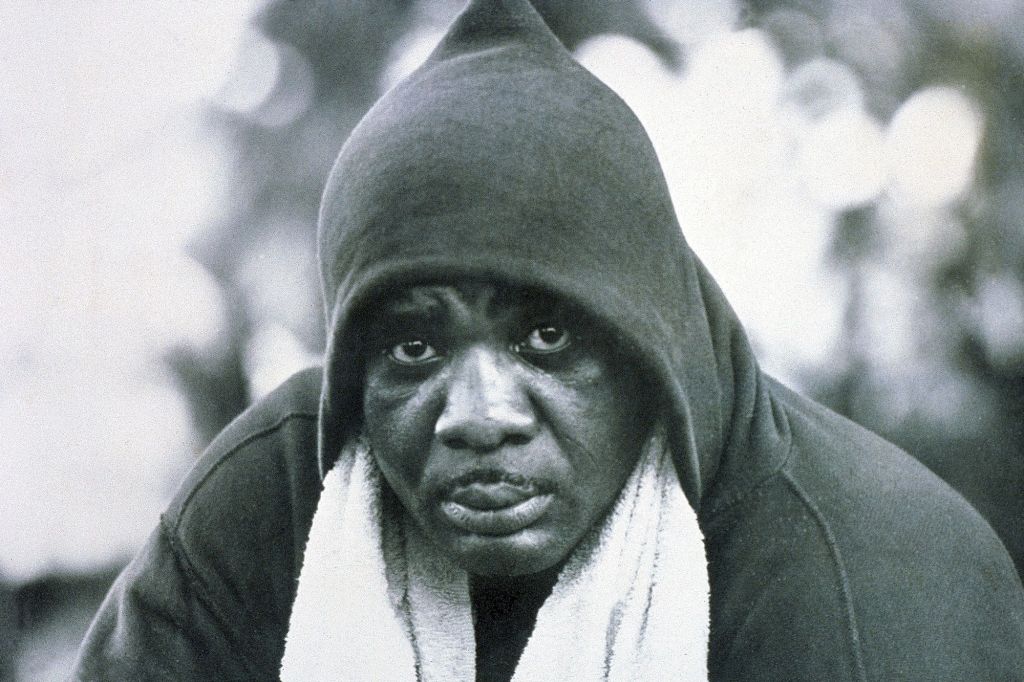

This post is an extraordinary examination of a troubled psyche. Based on the featured image, I first took this to be a post about Sonny Liston, a man whose violent life and mystery-shrouded death both deserve continued scrutiny, but no. This is about a man who was more troubled than Liston by far, yet whose ability to relay his dark thoughts exceeded all expectations. This is such a well-crafted and engaging article that I immediately found myself searching online for additional information after reading it. Well done!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks a lot for reading and commenting! I’m glad you enjoyed it and I hope you enjoy diving into some of Jones’ work. Sonny Liston is also a fascinating character. There is a biography of him by Nick Tosches that I want to read.

LikeLike